Surely you know what it's like to be disappointed by the movie version of a favorite book. I received the white edition of The Wizard of Oz on my fourth birthday in 1971. My mother read it to me, as well as the first few sequels, several years before I ever saw the movie on television. By that time the original tale and the illustrations by W.W. Denslow and John R. Neill were firmly entrenched in my mind. The movie simply didn't match the way I visualized Oz in my imagination. And as a child I was actually insulted that in the movie Dorothy's adventure was just a dream. After all, her visits to Oz in the books were most decidedly real, and for many years I used to hope against hope that maybe, just maybe, Oz was really real, and maybe, just maybe, I would get to go there some day and meet Dorothy and Ozma and everyone else.

But I digress.

Probably the thing I love the most about the movie is that it forever cemented The Wizard of Oz in popular culture. Thanks to Judy Garland, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke, Frank Morgan, all the little people, and the rest of the folks at MGM, no one will ever, EVER forget America's greatest fairy tale.

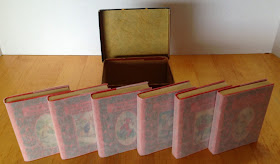

And so for those of you whose first love is the movie, I hope you especially enjoy the pictures I'm sharing today of my four MGM editions of The Wizard of Oz. As usual, I collect copies with dust jackets whenever possible.

The dust jackets of the American edition by Bobbs-Merrill are nearly identical. The first printing was issued in 1939, and the second printing came out circa 1942. The second printing is actually much scarcer than the first printing, but the first printing is still more valuable because, well because it's the first printing. As far as I know, the only difference between the dust jackets is that the price listed on the front flap was raised from $1.19 to $1.50.

Also the endpapers of the first printing show sepia tone stills from the movie, whereas the endpapers of the second printing are blank.

The two British editions were printed by Hutchinson circa 1940. Unlike the American edition, these are not two different printings. Instead they are two different binding variants of the same (and only) printing. The Hutchinson bindings look very different.

Binding B has cloth-covered boards, and the jacket art is different. In fact, Binding B is rather drab without the jacket.

The British editions seem to be considerably scarcer than their American counterparts, and they are especially hard to find in dust jackets. The British editions are also much harder to find in collectible condition. The paper-covered boards of Binding A are fragile, and both bindings have typically suffered from the damp climate in Great Britain. You can see the effects of climate especially well in the picture above of the Hutchinson Binding B. The spine shows discoloration, and the front board is slightly warped. One would usually expect to find a book that has been protected by its dust jacket to be in nearly pristine condition, but as you can see that wasn't the case with my Binding B. I would like to upgrade to a nicer copy of Binding B, but truth be told, this book is scarce in any condition. And the dust jacket is very rare. I'm sure there are other copies out there, but my dust jacket is the only one I've ever seen.